Cypriots on both sides of the north-south divide in Cyprus are rejoicing today after their respective Turkish and Greek Cypriot leaders announced full agreement on all points in last-minute talks brokered by the UN envoy to the island. The secret talks – which took place at an undisclosed location and also included representatives from Turkey, Greece and Britain – reportedly commenced yesterday evening and continued into the early hours of this morning. According to sources close to the negotiations, the deal outlines a six-month transition period which will see both the internationally recognised Republic of Cyprus and the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) merge to become a bizonal federation. Along with a rotational presidency, all citizens who lost their homes in the 1974 conflict will be handsomely compensated, with the UN pledging to secure financial support to settle decades-old land disputes. Turkey, meanwhile, says it has agreed to gradually pull its troops out of northern Cyprus and dissolve the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee, thus forgoing any legal rights to militarily intervene in the island’s affairs, on the condition that Cyprus joins the NATO bloc within the year. In return, Cyprus will remove its veto on Turkey’s EU accession, opening the way for Turkey to become an EU member within a time period of two years.

Now imagine that everything written in the above paragraph was actually true and not just a morally bankrupt way of me getting your attention. Imagine that a frozen conflict of almost half a century was really that easy to solve. Imagine Turkey, with its 80 million people and young, energetic, industrious workforce, as a fully integrated, liberal, progressive, Western-orientated economic powerhouse with excellent relations with its neighbouring European states, bulldozing its way to the heart of the EU. Imagine Istanbul, an ancient geopolitical centre of gravity, once again becoming a gateway along the Silk Road to the lucrative markets of Europe, thereby reclaiming its former glory at the junction where East meets West, and attracting the best, innovative young minds from all over the region. Imagine Turkish Cypriots having a true voice in Cyprus, in the Cypriot parliament, where they’d be able to challenge and veto unilaterally thought-out bills put forward by their Greek Cypriot counterparts, but never actually having to do so because Turkey’s prosperity would boost the entire Eastern Mediterranean region, and as a result, for the first time in centuries, Turks and Greeks would see their political and economic interests aligned.

In this imaginary world, a new political bloc would emerge on Europe’s southeastern front. Turkey’s soft power would naturally seep into the Levant, the Balkans and Eastern Europe, with Istanbul at its epicentre. Not before long, the people of Turkey, Cyprus, Greece, Albania, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and perhaps even Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan would start putting aside their differences and begin forming a new identity built upon mutual interests and benefits. There would be a Muslim-Orthodox reconciliation that would bring together a region that has barely known anything but unity for over 2,000 years, since the era of Alexander the Great right the way up until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. The last 100-200 years of strife would be brushed off as a mere hiccup on a timescale largely dominated by peace and cooperation. Distant nations such as Britain, France, the US, Germany and Russia would no longer be able to just barge into the region, arms swinging, and subject its people to austerity measures, debt-slavery, divisive strategies and intimidation tactics. The global power balance would shift away from the Northern Atlantic to the Mediterranean, which, unlike the West, is not heavily dependent on military prowess alone to maintain its stranglehold on world trade and international politics. A bloc in southeastern Europe which could expand to include the coastal states of North Africa and the Middle East would be a lot more versatile and self-sufficient, with easy-to-access land and sea trade routes, diverse agriculture, mineral-rich soils, abundance in fossil fuels, fresh water reserves, clean energy potential, and much more.

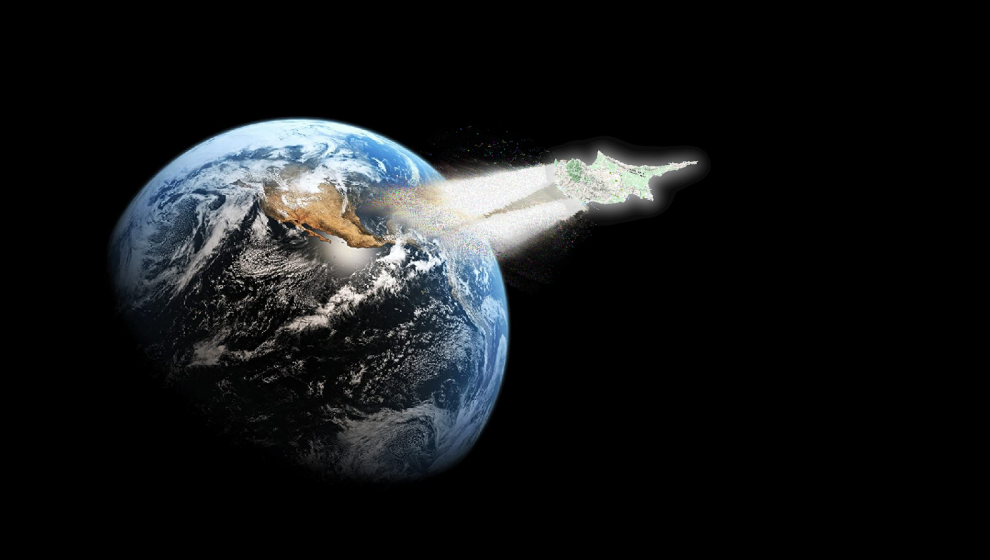

Sadly, these are the exact reasons why such a world, at least for the foreseeable future, will only ever be imaginary. The average commoner fails to fathom these factors when assessing the Cyprus problem. When put into isolation, to many the Cyprus problem seems easy to solve. Two sides negotiate, shake hands, Turkey goes home, everyone lives happily ever after, the end! However, we are, ever increasingly so, living in an interlocked, interdependent world. In reality, the Cyprus problem is attached to much larger geopolitical squabbles that an ordinary Cypriot, Turkish or Greek, cannot comprehend from the confines of their village coffee house, as they flip through the pages of a local newspaper between games of backgammon. Just as there is in Cyprus, there is a much greater status quo in the world, and such is the significance of this tiny island in the Eastern Mediterranean, that any change in the status quo there could bring about tremendous changes to the present-day world order. Likewise, in the same way that the status quo in Cyprus is being preserved by gatekeepers who are profiting from it, the global status quo also has its guardians.

Global Status Quo

Currently, on a wider scale, that status quo is this: Don’t let Turkey in, but don’t let it loose either. Keep it on the doorstep, chained to the porch. When it barks too much, hit it with a stick, but only hard enough to show it who’s boss. When it behaves, give it a pat on the head and throw it a bone. Don’t allow it to become strong enough to break in, but feed it just enough to ward off any would-be intruders. Then, when the intruders are no longer a threat, put it down and replace it with a more obedient dog. For this strategy to work, the world cannot allow Turkey to become civilised. Turkey is not allowed to become human, lest it earns the right to dwell among them. It must remain hairy, untamed, wild, and beastial. It has to fit into the role of the boogeyman, the scary monster you tell your children about to frighten them into conformity. Armenian genocide, Assyrian genocide, Greek genocide, Kurdish genocide, Alevi genocide. Cyprus invasion, Syria invasion, Iraq invasion, Libya invasion, Imia invasion. If you don’t finish your vegetables, the boogeyman is going to get you! If you let Turkey join the EU, they’ll take over Europe!

This is the story being played on repeat in countries around Turkey, as has been the case for the past 100 years, and even more so since Turkey started regaining enough strength to begin taking unilateral steps on its foreign policy. Since the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Turkey has for the most part been dancing to the beat of the West. It transformed from a theocratic monarchy to a secular democracy. It went on to forge good diplomatic relations with the West and become one of the first members of NATO. It even showed its loyalty to NATO by sending Turkish troops to fight against the communists in Korea. In the meantime, it was committing some of its worst human rights abuses in its history, including the violent suppression of rebellions in its southeast, and a military coup in 1960 which ended in the country’s democratically elected prime minister Adnan Menderes being executed. Back then, reactions to these atrocities were muted. Nobody was talking about genocides, or war crimes, or anything else Turkey stands accused of. These protests only started picking up traction in Western media around 2007, around the time of the assassination of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink. Funnily enough, it was also around the same time Turkey, under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, started resisting pressure from staunchly Kemalist, pro-Western army generals to curb what they deemed to be anti-secularist sentiments within the party. It was clear from that moment that Turkey was beginning to think outside of its borders, beyond a national level. It had suddenly developed a sense of religious belonging, in a region dominated by Muslims.

Even when Turkey sent its troops to Cyprus in 1974, the world reaction was nothing compared to when Turkey launched operations in northern Syria in 2016. The difference is that in 1974, Turkey, to a certain extent, was fulfilling a Western agenda in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Republic of Cyprus, under Archbishop Makarios, enjoyed warm relations with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. Although Makarios was a religious figure as well as the island’s president, he managed to strike an interesting balance which made him appealing to both conservative Orthodox Christians and left-leaning secular Greeks. This made him an ideal ally for the Soviets, who were desperate to find a way to the warm waters of the Mediterranean. At the same time, this made him a thaw in the side of the ultra-nationalist putschist military leaders of Greece, who saw Makarios’ insistence upon the independence of Cyprus as an obstacle to their aims of enosis, or annexing Cyprus to Greece. So, by ousting Makarios, the Greek junta inadvertently provoked a situation which resulted in the northern part of the island coming under the direct control of NATO member Turkey. The south, meanwhile, did not come under the direct control of Greece, but even after the Greek junta’s plan failed, Greece became the south’s number one trading partner. Thus, Greece secured a major foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean that it would not have had if Makarios had remained. NATO was also happy with the outcome because Soviet influence on the island was minimised as the new situation meant nationalists on both sides of the divide would feed off each other, and one thing both Turkish and Greek nationalists had in common at the time was that they were both anti-communist, anti-Soviet. Therefore, throughout the Cold War, the post-1974 status quo in Cyprus served the NATO agenda, as it still does today with the Russians once again vying for influence in the region.

Western Hegemony vs Eastern Mediterraneanism

But what if Turkey didn’t intervene in 1974? What if they had welcomed the new rulership of Cyprus and allowed the island to be annexed by Greece? Of course everyone knew this scenario was impossible. Turkey had to act, because for Turkey, to allow such a thing would have meant surrendering their direct access to the open seas of the Mediterranean to Greece. If Turkey had not intervened in Cyprus, they would have certainly conducted military operations elsewhere, such as the Dodecanese islands, to secure a maritime corridor. The Greek junta were indeed foolish to believe they would get away with the 1974 coup scot-free. But what if Turkey was so incapacitated at the time that they couldn’t launch a military operation even if they wanted to? That would have probably been an indication that Turkey is not capable of defending its own coastline, and invited further Greek claims to mainland Anatolia. Greece would have annexed Cyprus, then launched an assault on Izmir, before besieging Istanbul and finally reclaiming Hagia Sophia for the Christian world. The ‘megali idea’ of Greater Greece would be complete and the glory days of the Byzantine Empire would be revived. That easy, right? Wrong!

In such an event, Greece would become the new target of the Western powers. Greece would replace Turkey as the boogeyman. We’d suddenly be hearing about the genocide of Turkish Muslims and Jews in the Penopolese peninsula at the hands of Greek militias in 19821. We’d be hearing about the expulsion of Cretan Muslims in 1897. There would be international condemnations of the Greek occupation of Cyprus, and protests against Greek human rights abuses against Turks in Anatolia. Greece would be hit with sanctions and calls to be evicted from NATO. It would be accused of supporting ultra-orthodox terrorist groups who carry out attacks on secular liberals and religious minorities. Why? Because Greece would be doing the one thing the West in particular does not want to see – creating an Eastern Mediterranean superpower that does not have to bow down to Western hegemony. In other words, Greece would be in a position to say “no”, and to tell the EU to take its austerity measures and go to hell. Countries like the US, Britain and France would have to ask Greece extra nicely to conduct military operations in the region, to which Greece could reply by making demands on areas like the Balkans. The Catholic, Protestant and Evangelist alliance would be at the mercy of the Greek Orthodox nation, which could eventually go on to decide it gets along a lot better with its Russian Orthodox co-religionists and decide to seek out a different set of allies. Naturally, Grecophobia would become the new Turcophobia, and Orthodoxophobia would become the new Islamophobia.

The truth is, the global status quo is neither pro-Greek nor pro-Turk. It is neither anti-Greek nor anti-Turk. If the lands of Turkey, Greece and Cyprus were inhabited by the Chinese and Japanese instead of Turks and Greeks, the same conflict would occur. The real issue the global status quo has is not with any particular race or religion, but with the Eastern Mediterranean as a region. The present-day world order cannot afford to allow any one nation to grow dominant in the region. The region must stay divided upon the foundations of a very delicate power balance. When one state becomes unruly, another state is used to keep it in check. When one state becomes too powerful, the other states unite to weaken it. When one alliance gets too dangerous, another alliance emerges to split it up. Cyprus particularly lies on one of the many civilisational fault lines carved into the region. These tectonic cracks, which began to appear during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, serve to keep Western hegemony relevant to the region, with the West playing the role of devil’s advocate. They also make it impossible for a rival competitor, Russia for instance, to deploy its own strategy in the region. To erase those divides, therefore, contradicts the Western geopolitical agenda. For this reason, one cannot expect the West to sincerely support any peace deal in Cyprus. Likewise, one should always be weary whenever the West offers its backing to one side over another in diplomatic disputes. The West does not want to see any unity in the Eastern Mediterranean, neither Turkish-led, nor Greek-led. Any kind of peaceful Turkish-Greek reconciliation would be even more of a nightmare for the West.

Carving the Turkey

If anything, the West seeks even further division, starting with the splitting up of Anatolia and the eradication of the Turkish national identity. These will not be pieces for others to pick up, not the least Greece. Rather, the plot would be to initiate a Balkanisation of Anatolia, with each region being socially engineered to develop its own national identity and sense of belonging. This would have been the reality today if the 1920 Treaty of Sevres stood the test of time. Turkey today would have been carved up into different regions, each with its own language. The only state left for Turks would have been a small patch of land in northern Anatolia – just a nation of fishermen paddling around in circles in the Black Sea.

If anything, the West seeks even further division, starting with the splitting up of Anatolia and the eradication of the Turkish national identity. These will not be pieces for others to pick up, not the least Greece. Rather, the plot would be to initiate a Balkanisation of Anatolia, with each region being socially engineered to develop its own national identity and sense of belonging. This would have been the reality today if the 1920 Treaty of Sevres stood the test of time. Turkey today would have been carved up into different regions, each with its own language. The only state left for Turks would have been a small patch of land in northern Anatolia – just a nation of fishermen paddling around in circles in the Black Sea.

Had the Turkish coup attempt of July 2016 gone according to plan, Turkey would have undoubtedly entered a bloody civil war that would have lasted at least a decade. It would have become a sitting duck for foreign intervention whereby the Treaty of Sevres could be put back on the table. One can only guess where this would have left the Cyprus problem, but something tells me it would not have been the end of it, because the fault line between Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots would not have lost its value. Instead, we would have been more likely to see another actor move in to fill the void Turkey left behind. Perhaps Syria, Italy, or even a brand new state with access to the Mediterranean (dare I say Kurdistan) would have stepped in. Ultimately, the Greek Cypriots would not have been allowed to move in to dissolve the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The Cyprus problem would have continued to exist, just in an altered way. The beneficiaries of the island’s status quo would have seen to that.

So, with all this going on in the background, is it really possible to solve the Cyprus problem? I’d say there is, but only when we stop seeing it as the Cyprus problem, because in reality, there is no Cyprus problem. There is, and only ever has been, an Eastern Mediterranean problem. If we want to solve the problem, first we have to see it for what it really is. After correctly diagnosing the illness, then we can prescribe the correct medicine. To change the status quo in Cyprus, there must first be a shift in the global status quo. Cypriots, Turks and Greeks, could attempt to initiate that by themselves, but until there is a wider awakening in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly in Turkey and Greece, negotiations would always be doomed to fail. Truth be told, I’m not holding my breath on it, but instead of settling for being a victim of circumstance, I’ve chosen to understand and come to terms with it.

It is indeed a sad, sad time to be a native Eastern Mediterranean.

the Editor-in-Chief of Radio EastMed